Baumol’s Cost Disease & Broadway

Broadway’s finances have evolved dramatically since 2010, and this issue is once again front and center as Actors Equity Association (AEA) and The Broadway League negotiate the Equity Production Contract (the agreement that contains the terms of employment for stage managers and actors on Broadway). I’ve been sent this article written by Michael Paulson in the New York Times by several folks, including my own Mom, who subsequently told me: “I’m worried there’s no future for you in theater” (thanks, Mom!).

The tension between AEA and The Broadway League is intense, with both sides holding valid concerns. Actors, musicians, and crew are working harder than ever — longer rehearsal periods, more complex productions, constant juggling of side jobs. On the producer side, budgets are ballooning, ticket prices feel unaffordable, and the idea of a show recouping (let alone profiting) seems to be impossible. At the core of this paradox: Broadway’s fundamental economics haven’t changed. One performance, one audience, one ticket per seat. This makes Broadway a textbook case of a larger economic trend: Baumol’s cost disease.

Baumol’s cost disease, introduced in the 1960s (and to me in a college statistics class) describes what happens when wages rise across the broader economy, but productivity doesn’t rise equally. A factory worker can make 100 cars today instead of 10, and a programmer can automate tasks for thousands of users. Their productivity increases, and that higher output makes it easier for companies to pay rising wages.

But, in theater, productivity is flat: it still takes a dozen actors about 2.5 hours to perform Hamlet (barring some new, avant-garde Jamie Lloyd production of it). The number of performances per week is still eight. But, while wages across the economy still rise, productivity doesn’t change, simply because theater can’t scale its output in the same way. With this, costs climb without any corresponding increase in efficiency.

To be crystal clear: “productivity”/”efficiency” in this sense does not mean that actors, musicians, or stagehands aren’t working ‘hard enough’. It’s the opposite: their work simply can’t be automated or scaled without losing what makes it such a unique artform.

And that’s the fundamental squeeze — as Broadway shows become more labor-intensive (bigger ensembles, harder roles, elaborate stagecraft), the economics can’t scale to match.

To see this dynamic in action, we can track Broadway’s costs, revenues, and ticket prices in the past two decades, comparing against inflation and wages in New York City.

Capitalization: The Cost to Open a Show

Producing a show on Broadway requires a massive upfront investment, and it has only gotten more expensive.

In 2010-2011, the capitalization for a musical averaged around $9.7mm, with plays around $2.4mm.

In 2019 (pre-COVID), musicals hovered around $15mm and plays around $4mm.

In 2023-2025, musicals can be anywhere from $20mm to $25mm (on average), and plays from $4.5mm to $6mm.

Why costs have gone up:

Physical production elements (set, props, costumes, lighting, sound) account for a large chunk, usually around 20%+ of budgets, and their prices have risen with materials inflation (i.e lumber costs surging post-2020). Design ambitions have grown as well, with tech-heavy staging now the norm for big musicals.

Extensive out-of-town tryouts and development workshops are increasingly common, as are fees for top creative talent and star performers.

Marketing and advertising for a Broadway show are also colossal, as shows continue to vie for audience attention in a crowded entertainment market.

Producers have built in larger reserves to keep shows afloat during weak-performing weeks.

Note: Exact Broadway production costs aren’t publicly available. The numbers shown reflect a mix of reported figures and inferred benchmarks.

Weekly Running Costs

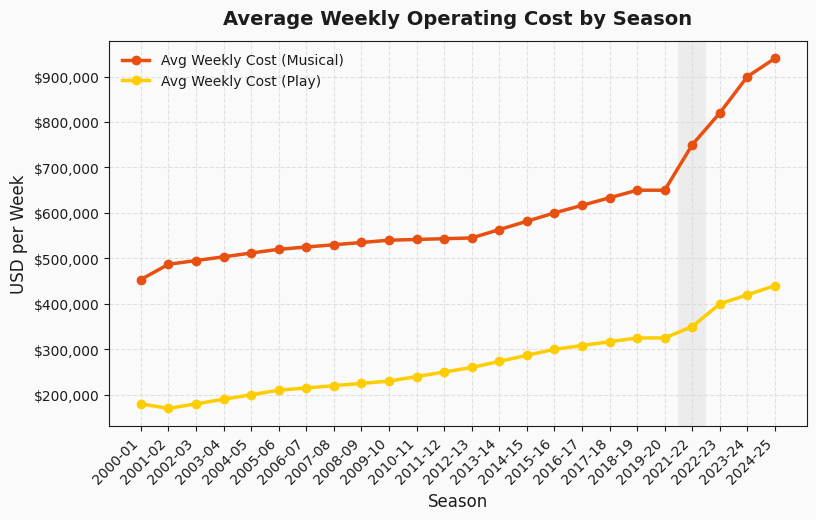

On top of the initial costs required to mount a production, each week, shows face weekly recurring expenses.

In 2010-2011, the weekly “nut” for musicals averaged $590k/week; plays $278k/week

Today:, musicals are ~$700k-$900k/week (on average); plays ~$450k-600k

Big drivers include:

Labor, with salary, taxes, and benefits constituting well over half of a show’s weekly running expenses.

Theater Rent: Broadway theater owners charge rent as a fixed expenses plus a gross percentage.

Marketing: Advertising is essential, even for hit shows, which can include press agents, advertisement buys, and other promotions.

Insurance & Overhead: A fixed line item that rarely shrinks.

Many large musicals now need to gross over $1mm a week just to see any profit.

Note: Exact Broadway production costs aren’t publicly available. The numbers shown reflect a mix of reported figures and inferred benchmarks.

Ticket Prices and Revenue

Because The Broadway League publishes weekly box office statistics, ticket prices and revenues give us the clearest window into Broadway’s financial story.

2010-2011: Average ticket price hovered around $86.

2018-2019: $124

2024-2025: $129

This results in ~50% growth in a little over a decade. Inflation (CPI) rose 18% in the same period, while NYC private-sector wages rose around 20%. Broadway ticket prices have far outpaced both.

The “Avg Ticket (Nominal)” line reflects the reported ATP per Broadway season, while the “If Ticket Tracked CPI” models a world where ticket prices rose only at the rate of consumer inflation.

By indexing everything to 2000, this chart shows how Broadway ticket prices have raced ahead of both inflation and wages.

Why This is Baumol’s Cost Disease in Action

Costs (capitalization + weekly nut) have risen far faster than inflation.

Ticket prices have risen faster than both inflation and NYC wages.

Output (number of seats x number of shows) has not changed.

Even as production become more technically demanding and labor-intensive, none of that creates more efficiency per week. The financial math stays stubborn: high costs, limited revenue capacity, rising prices.

Where This Leaves Us

It’s tempting to say that producers are greedy, or that unions are too rigid. But Baumol’s cost disease reminds us: everyone is right to feel squeezed.

Artists: Wages haven’t kept pace with NYC’s cost of living, let alone the higher standards required for Broadway-quality performance

Producers: Weekly nuts demand ticket prices that alienate audiences and make raising capital difficult

Audiences: Affordability feels out of reach; the only people consistently willing to spend on new/adventurous work are die-hard theater fans (a passionate base, but not a sustainable audience for long-term success)

How to Fix It

Over the past few days, I’ve heard perspectives from everyone — friends performing grueling tracks onstage eight times a week, and young producers like me who want to champion bold, new work. But if the economics don’t hold, it becomes harder to take risks, and the kinds of Broadway shows that get made will narrow instead of expand.

What unites us, though, is simple: we all want theater to thrive.

I’ll be the first to admit that I don’t have a neat solution here. But I do believe that the first step forward is more transparency and education about the economics of our industry. Broadway’s financial mechanics are rarely explained openly, which fuels blame and misunderstanding.

We should start encouraging producers to take time to walk their creative teams through the financial realities of a production. Conservatories should treat theater economics as core training, alongside acting, music, and dance. Investors should be equipped with clearer information and data about a production, so they can make smarter decisions and, in turn, expand the range of shows that can make it to the stage.

(A few places that already are doing this: The Business of Broadway, Theatre Producers of Color, Producer Hub, among many others).

At the end of the day, artists, producers, theater owners, audiences — we’re all collaborators in building a sustainable theatrical economy. The economics are challenging, yes, but they also remind us that the human effort of live performances can’t be automated or scaled away. That’s what makes theater expensive, but also beautiful. If we work together with clarity and creativity, we can take steps forward to create a theatrical environment that is vibrant, accessible, and full of daring, unforgettable work. In the textbooks, it’s Baumol’s cost disease, but it’s also proof that Broadway still runs on people, not algorithms.

Sources & References

Broadway finances aren’t fully transparent, so this post draws on a mix of public data, trade reporting, academic studies, and producer commentary.

Broadway League - publishes grosses, attendance, and average ticket prices (Broadway League Statistics)

Consumer Price Index (CPI) - BLS CPI Data

NYC Wage Data - New York State Department of Labor and NYCEDC reports

Loeb & Loeb - The Basics of Investing on Broadway

Ken Davenport - The Producer’s Perspective

Ken is a strong example of a producer who prioritizes transparency, consistently sharing data with investors and making openness a core part of his producing approach.

The Hustle - “The Economics of Broadway Shows”

Forbes - “Skyrocketing Broadway Show Budgets Scare Producers”

Marc is another great example of someone who prioritizes transparency — and is perhaps one of the smartest people studying Broadway economics.

Bucknell University - Study on return on investment in Broadway musicals

EBSCO - Baumol’s Cost Disease